the Armenian Genocide

The Young Turks and the Rise of Nationalism

From Promised Reform to Calculated Erasure

In 1908, the Young Turk Revolution marked what many believed would be a new era for the ailing Ottoman Empire. Spearheaded by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the revolution deposed Sultan Abdul Hamid II and installed a constitutional regime that vowed to restore justice, modernize the state, and uphold equality among all ethnic and religious groups. Among Armenians and other non-Muslim minorities, there was cautious optimism. Centuries of repression, massacres, and broken promises had left deep scars—but the language of reform brought a brief sense of hope.

That hope was short-lived.

Behind the veneer of liberalism, the CUP leadership harbored a radical vision: the transformation of the multi-ethnic Ottoman Empire into a homogenous Turkish nation-state. This vision, fueled by ultranationalism and a fear of imperial disintegration, would ultimately become one of the ideological foundations of genocide. Following the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, in which the empire lost vast territories to newly independent Christian nations, panic set in. The loss of land was interpreted not merely as a geopolitical failure but as evidence of betrayal by non-Muslim populations. Armenians, despite generations of loyalty and service to the empire, now found themselves labeled as internal enemies.

Economic Prominence and Growing Paranoia

By the early 20th century, Armenians played a disproportionately influential role in the empire’s urban economy—particularly in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), where they made up around 15% of the population by 1913 (roughly 163,670 people). Their presence was not just numerical; it was deeply entrenched in the empire’s financial, artisanal, and commercial fabric.

- In Constantinople, Armenians dominated sectors such as jewelry manufacturing, banking, and textiles. Entire neighborhoods like Galata and Hasköy were hubs of Armenian economic life, with their own financial institutions and craft guilds.

- In Aleppo, merchant dynasties like Khwaja Petik Chelebi and his brother Khwaja Sanos Chelebi had, since the 16th century, commanded vast silk trade routes spanning Anatolia, Persia, and India, underscoring a long history of Armenian commercial ingenuity and resilience.

But this prominence came at a cost. Many within the Muslim population—and crucially, among Ottoman leaders—viewed the Armenians’ success with suspicion and resentment. Economic jealousy merged with ethnic nationalism, casting Armenians as an obstacle to the CUP’s dream of a “Turkified” empire.

The Road to Genocide

As World War I loomed, this combination of nationalist ideology, economic envy, and military defeat created a volatile atmosphere. The CUP regime, driven by paranoia and emboldened by a collapsing international order, began to see extermination not as a crime—but as statecraft.

Armenians were no longer viewed as citizens but as a fifth column, a convenient scapegoat for internal decline. The groundwork had been laid. The rise of the Young Turks, far from ushering in democratic reform, had become the ideological incubator of genocide.

The Outbreak of World War I and the Implementation of the Armenian Genocide (1915-1923)

With the advent of World War I in 1914, the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers, engaging in battles on multiple fronts. As the war progressed, the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) sought to consolidate its power and eliminate perceived threats to its nationalist agenda. The Armenian population, which had long been marginalized and subjected to discriminatory policies, became a convenient scapegoat. Ottoman authorities accused them of harboring sympathies for the Russian Empire, a claim rooted in little more than the existence of Armenian communities on both sides of the Ottoman-Russian border.

This accusation was not only baseless but deliberately manufactured as part of a broader strategy to demonize and dehumanize the Armenian population. The Ottoman leadership knew that wartime propaganda could be an effective tool in inciting fear and hostility among the broader Muslim population, thereby justifying their premeditated plans for mass deportations and extermination. The accusation of disloyalty served as a pretext to frame Armenians as an existential threat, paving the way for their systematic destruction.

In reality, Armenian political and religious leaders had made numerous efforts to demonstrate loyalty to the Ottoman state, and the majority of Armenians, including those in the Ottoman military, had no involvement in any subversive activities. Nonetheless, the CUP’s propaganda machine successfully painted Armenians as traitors, a narrative that was used to rationalize their forced marches into the Syrian desert, mass executions, and other atrocities.

This falsification was not an isolated incident but a classic case of state-sponsored incitement, designed to prepare the populace for genocide. By portraying Armenians as enemies within, the Ottoman regime sought to ensure public acquiescence, if not outright participation, in the genocide that followed.

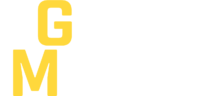

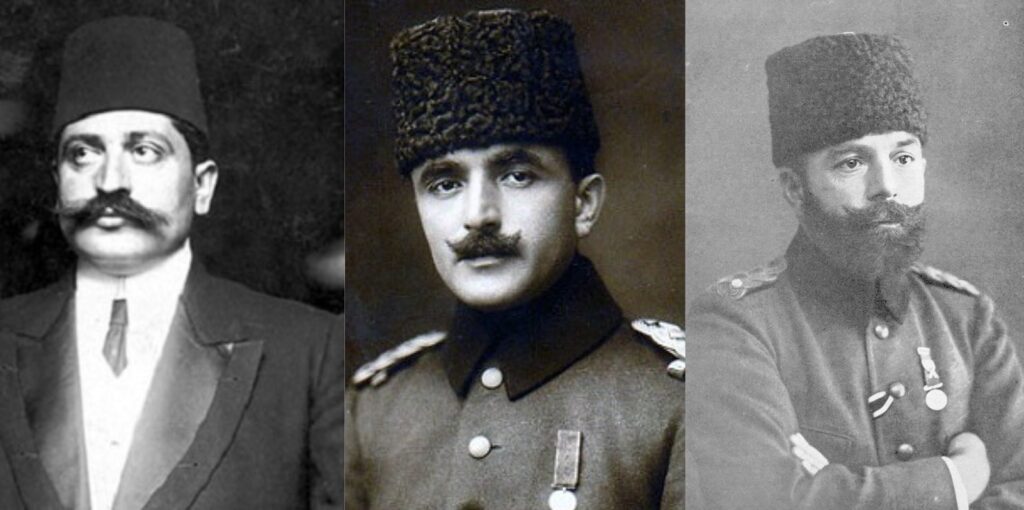

THE MASTERMINDS OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE

The Armenian Genocide was meticulously planned and executed by the highest ranks of the Ottoman government, particularly the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). At the center of this orchestrated extermination were the so-called “Three Pashas”—Mehmed Talaat Bey (later Talaat Pasha), Ismail Enver Pasha, and Ahmed Djemal Pasha—who wielded absolute power over the empire during World War I. Talaat Pasha, the Minister of the Interior and later Grand Vizier, was the chief architect of the Genocide. He personally issued orders for mass deportations and executions, overseeing the logistical network that ensured the annihilation of the Armenian population. Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, used the pretext of military necessity to justify the slaughter, blaming Armenians for the Ottoman Empire’s military failures. Djemal Pasha, the Governor of Syria and Minister of the Navy, imposed brutal measures against Armenian refugees in the Syrian deserts, particularly in Deir ez-Zor, where thousands perished under his direct supervision.

Beyond these three, other high-ranking officials played pivotal roles in carrying out the Genocide. Dr. Mehmed Nazim, a leading figure in the CUP and an ideological fanatic, was one of the primary proponents of racial extermination, openly advocating for the destruction of Armenians as a means to create a homogenous Turkish state. Behaeddin Shakir, the head of the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization), oversaw death squads composed of criminals and paramilitary units, which carried out mass killings with ruthless efficiency. These operatives were responsible for some of the most gruesome massacres, including the drowning of Armenian women and children in rivers, the burning of entire villages, and the operation of primitive gas chambers in Deir ez-Zor, where victims were asphyxiated in caves set on fire.

After the war, these masterminds of genocide fled the collapsing Ottoman Empire. Mehmed Talaat Pasha was assassinated in Berlin in 1921 by Soghomon Tehlirian, an Armenian survivor who carried out the execution as part of Operation Nemesis, a clandestine campaign to bring Ottoman war criminals to justice. Ismail Enver Pasha was later killed in battle in Central Asia, while Ahmed Djemal Pasha met his end in an assassination in Georgia in 1922. Though some faced retribution, many other perpetrators escaped consequences, with some even reintegrating into the Turkish Republic’s political and military elite. Their legacy of genocide denial continues to shape modern Turkish policy.