the Armenian Genocide

The Emptying of Historic Armenia: The Final Solution to the Armenian Question

By 1923, after eight years of orchestrated extermination, over 1.5 million Armenians had been systematically murdered, and the Armenian presence in their ancestral homeland had been all but erased. What began on April 24, 1915, with the mass arrest of Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople, culminated in the complete depopulation of Western Armenia—a region Armenians had inhabited for over three millennia.

This was not merely mass murder. It was a Final Solution: the forced removal, extermination, and cultural annihilation of Armenians from the very lands where their civilization was born—lands where they had built thousands of ancient churches and monasteries, preserved sacred manuscripts, and contributed to the intellectual and economic life of the Ottoman Empire.

Millions of Armenian homes, schools, and businesses were destroyed, looted, or confiscated, and entire towns were emptied and repopulated. Churches were converted into mosques or army outposts. Cemeteries were desecrated. Place names were changed, and Armenian history was deliberately erased from maps, books, and public memory.

What was also lost were generations of Armenian minds—scholars, writers, poets, teachers, physicians, and craftsmen—whose lineage of thought, culture, and innovation was abruptly cut short. The genocide did not only kill bodies; it shattered centuries of accumulated knowledge, creativity, and intellectual tradition.

The goal was clear: to leave behind no Armenians, no memory, and no return. It was not only the extermination of a people—but the systematic obliteration of a civilization that had flourished for thousands of years.

The survivors, many of whom were orphaned children or destitute refugees, scattered across the world, forming the Armenian Diaspora in countries such as the United States, France, Argentina, Lebanon, and Canada.

The Role of Foreign Observers

The world was not blind to this erasure—but it did little to stop it. Foreign diplomats, journalists, and relief workers provided crucial documentation of the Armenian Genocide. U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau Sr., was one of the most outspoken figures, repeatedly warning the U.S. government about the Genocide. Eyewitness reports from missionaries and journalists, such as Armin T. Wegner and the American Committee for Relief in the Near East, helped provide contemporary evidence of the atrocities.

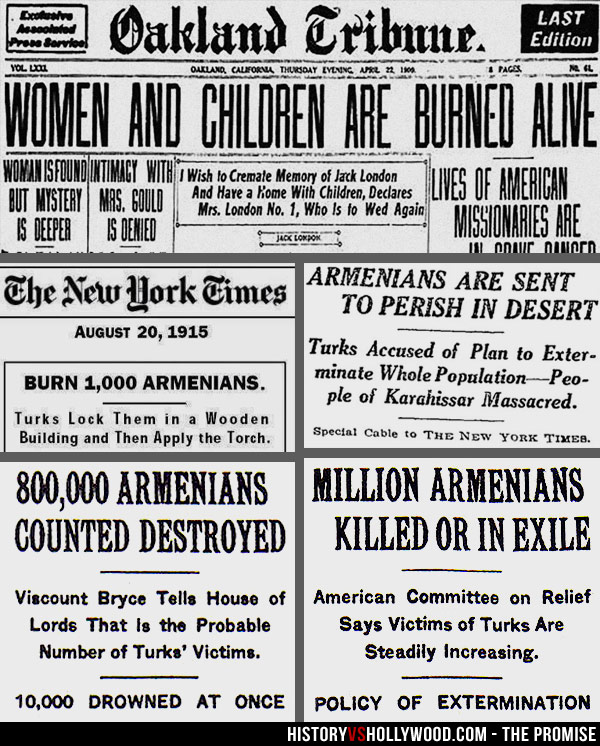

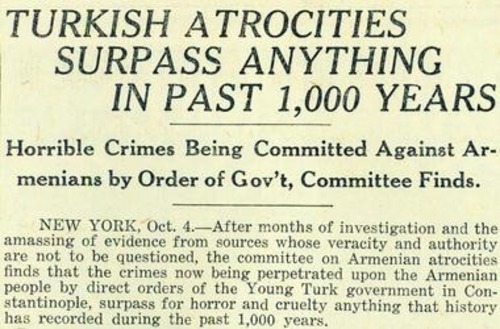

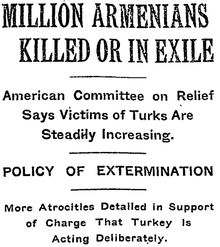

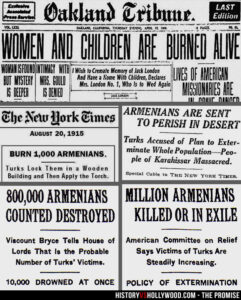

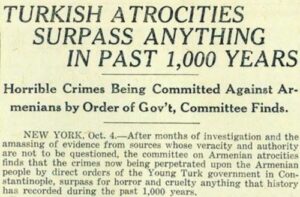

The horrors of the Genocide were widely reported in the international press, with The New York Times alone publishing over 145 articles on the massacres between 1915 and 1916, many carrying explicit titles such as “Wholesale Massacres of Armenians by Turks” and “Appeal to the Ottoman Empire to Stop Massacres.” These reports described in grim detail the death marches, mass executions, and starvation that Armenians endured, dispelling any notion that these events were isolated or exaggerated. The global response, though largely limited to humanitarian aid at the time, underscored the undeniable truth that the world was watching, even as governments hesitated to intervene.

Among those who documented the Genocide, Armin T. Wegner, a German soldier and medic stationed in the Ottoman Empire, took some of the only known photographs of the atrocities—images that would later serve as undeniable evidence of the Genocide. His smuggled photographs depicted emaciated Armenian refugees, mass graves, and the unimaginable suffering in the concentration camps of Deir ez-Zor. Similarly, the American diplomat Leslie Davis, stationed in Harput, meticulously chronicled the mass killings he witnessed, his reports emphasizing the scale and premeditated nature of the extermination.

Relief organizations also played a crucial role in documenting and alleviating Armenian suffering. The American Committee for Relief in the Near East (later known as Near East Relief) spearheaded one of the largest humanitarian efforts of the early 20th century, raising over $100 million (equivalent to billions today) to aid survivors. Their efforts helped rescue thousands of Armenian orphans who had been left to die in the deserts of Syria. Countless missionaries and aid workers risked their lives to smuggle out testimonies, photographs, and detailed reports of what they had witnessed.

Despite these efforts, political inaction and geopolitical interests prevented meaningful intervention at the time. Still, the records they compiled would later serve as the foundation for historical recognition of the Armenian Genocide. Morgenthau’s memoir, Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story, and Wegner’s harrowing photographs became pivotal pieces of evidence, referenced by scholars, activists, and even Raphael Lemkin—the legal scholar who later coined the term genocide—as undeniable proof of the systematic annihilation of the Armenian people.

Today, these testimonies remain crucial in the ongoing fight for global recognition of the Genocide, challenging denialist narratives and ensuring that the voices of those who bore witness are never silenced.

Colonialism, Erasure, and the New Turkish Republic

The establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 finalized this process. Under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Turkish state continued the policies of denial and demographic engineering that began under the Young Turks. Armenian lands were redistributed, properties confiscated, and the memory of a once-thriving civilization suppressed under nationalist ideology.

This was not only genocide—it was colonialism through ethnic cleansing. The Armenian highlands were repopulated by Muslim refugees from the Balkans and Caucasus, and the very existence of Armenians in Anatolia was erased from textbooks, monuments, and political discourse. The land itself was renamed, reimagined, and reclaimed—with no trace of the people who once called it home.