The Baku Pogroms of Armenians (January 1990)

State-Enabled Ethnic Violence During the Collapse of the Soviet Union

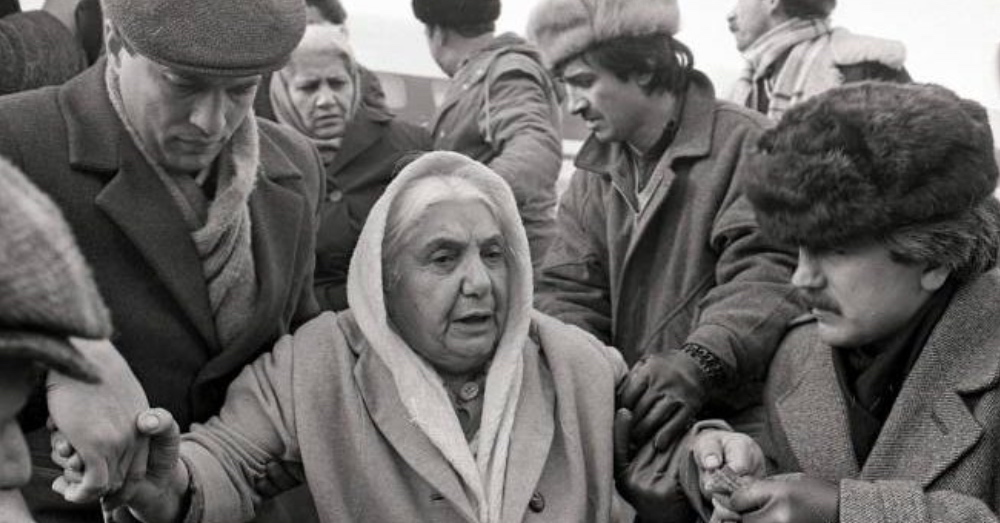

The Baku Pogroms refer to a week-long wave of organized violence, looting, and killings carried out against the Armenian population of Baku, the capital of Soviet Azerbaijan, from January 13 to 19, 1990. Coming just two years after the Sumgait Massacre, the Baku Pogroms marked one of the most brutal acts of ethnic cleansing against Armenians in the late 20th century. Thousands were forcibly displaced, hundreds injured, and dozens tortured or killed — often in full view of neighbors and security forces.

While the Soviet Union was unraveling, Azerbaijani nationalist movements surged in momentum. This violence was not spontaneous but emerged from growing anti-Armenian sentiment, state propaganda, and the unresolved tensions surrounding the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Historical Background

By the late 1980s, ethnic Armenians in Azerbaijan were under increasing threat due to rising Azerbaijani nationalism and unresolved territorial claims over Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh), a majority-Armenian region seeking reunification with Armenia. Following the Sumgait (1988) and Kirovabad (1988) pogroms, Baku remained one of the last major cities in Azerbaijan with a significant Armenian population — estimated at between 35,000 and 50,000 people.

Amid political chaos, the weakening of central Soviet authority, and inflammatory rhetoric from local nationalist groups, Baku’s Armenian population became a prime target.

Timeline of the Pogrom

January 13, 1990 — Mass protests erupt in Baku’s Lenin Square, led by the Popular Front of Azerbaijan. Calls for violence against Armenians escalate. By evening, groups of armed mobs begin attacking Armenian homes and apartments.

January 14–18 — Systematic assaults intensify. Armenians are dragged from their homes, beaten, raped, mutilated, and in many cases burned alive. Armenian-owned property is looted and destroyed. Hospitals and emergency services are overwhelmed and largely unresponsive.

January 19 — Soviet troops finally intervene and declare martial law — after nearly a week of unchecked violence. By this time, most of Baku’s Armenian population had either fled, gone into hiding, or been killed.

Casualties and Displacement

The official death toll remains disputed. Soviet reports claim approximately 90 fatalities, but Armenian sources and human rights organizations estimate significantly higher numbers, citing numerous unreported murders, missing persons, and undocumented burials.

More than 250,000 Armenians were ultimately displaced from Azerbaijan between 1988 and 1990. The Baku Pogrom effectively ended centuries of Armenian presence in the city.

Eyewitness Accounts and Human Rights Reports

Survivor testimonies describe terrifying scenes of neighbors turning on Armenian families, and local police either standing by or participating in attacks. International human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch, documented the atrocities and criticized the delayed Soviet response, as well as the failure of Azerbaijani authorities to protect their Armenian citizens.

One survivor wrote:

“They came with lists. They knew who was Armenian. The worst part is, they weren’t strangers — they were people we’d lived next to for years.”

International Reaction and Impunity

The global response was muted. Preoccupied with the collapse of the Soviet Union and rising Cold War tensions, international powers largely ignored the pogrom or treated it as a tragic side effect of regional instability.

Very few individuals were arrested, and those who were received minimal sentences. Many perpetrators were later hailed as national heroes in Azerbaijan. The Baku Pogrom became a symbol of impunity, cementing a pattern of denial, glorification of violence, and lack of justice for crimes against Armenians in Azerbaijan.

Historical Significance

The Baku Pogroms marked the culmination of a campaign to ethnically cleanse Armenians from Azerbaijan. Along with the Sumgait and Kirovabad massacres, Baku’s events demonstrated that anti-Armenian violence was not isolated or accidental — it was a pattern of targeted, state-enabled persecution.

For many Armenians, Baku became a second Genocide — this time within living memory, without war, and without punishment.

Legacy and Memory

Today, the Baku Pogroms remain largely unacknowledged by the Azerbaijani government. Armenian survivors live in exile, scattered across Armenia, Russia, Europe, and North America, many never able to return to the homes they lost. In Azerbaijan, the events are either erased from public discourse or justified as part of a nationalist struggle.

The Baku Pogroms were not an isolated incident. Like the violence in Sumgait and Kirovabad, they form part of a coordinated effort to enact a Final Solution to the Armenian presence in Azerbaijan. As a Turkic state ideologically and politically aligned with Turkey, Azerbaijan has adopted the same methods of ethnic cleansing — targeting Armenians through systemic propaganda, mob violence, and forced displacement. These actions reflect a persistent and dangerous continuity with the policies that fueled the Armenian Genocide.

At the Armenian Genocide Museum of Canada, we preserve the memory of the Baku Pogroms as part of the broader continuum of Armenophobia and ethnic violence, which has spanned generations and borders. The pogrom is not only a historical tragedy — it is a modern warning of what happens when hate propaganda, political instability, and denial converge.