The First to Suffer, The Last to Be Remembered: Honouring Armenian Women in the Genocide

Between 1915 and 1923, during the Armenian Genocide, the Ottoman Empire systematically exterminated 1.5 million Armenians. Women were not collateral victims; they were direct targets of destruction, singled out for gendered violence that combined murder, sexual assault, enslavement, and cultural erasure.

After the arrest and execution of Armenian men, women and children were left defenceless. Soldiers, gendarmes, and paramilitary groups looted homes and abducted women. Pregnant women were sometimes cut open with bayonets, with soldiers and bystanders betting on the sex of the unborn child. Women were hung by their hair from trees; Turkish and Kurdish men used them for target practice, throwing bayonets and knives as part of brutal games.

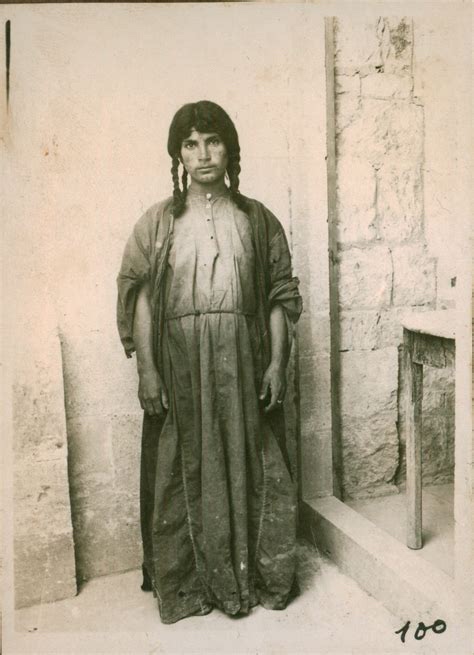

Mass rape was widespread. Rape was used systematically as a weapon of war, not only to brutalize but to erase Armenian identity through forced pregnancies, forced religious conversions, and abductions. Girls as young as 12 were seized from death marches and sold in slave markets or forcibly married to Turkish, Kurdish, or Arab men. Women were tattooed, branded, or marked to signify their new ownership. Many were forcibly converted to Islam, renamed, and prevented from speaking Armenian.

The death marches through the Syrian deserts were sites of mass extermination. Women and children were forced to walk for weeks under the sun, deprived of food and water. Mothers were often forced to abandon their children on the roadside when they could no longer carry them. Eyewitness accounts describe women driven to madness, tearing at their clothes, eating grass, or collapsing from exhaustion. Sexual violence accompanied the marches; gendarmes and bandits assaulted women openly along the routes.

Survivor testimonies document women who chose suicide over capture. Groups of women and girls threw themselves into rivers, off cliffs, or into wells to avoid rape and enslavement. In some cases, mothers smothered their own children to spare them from torture or starvation.

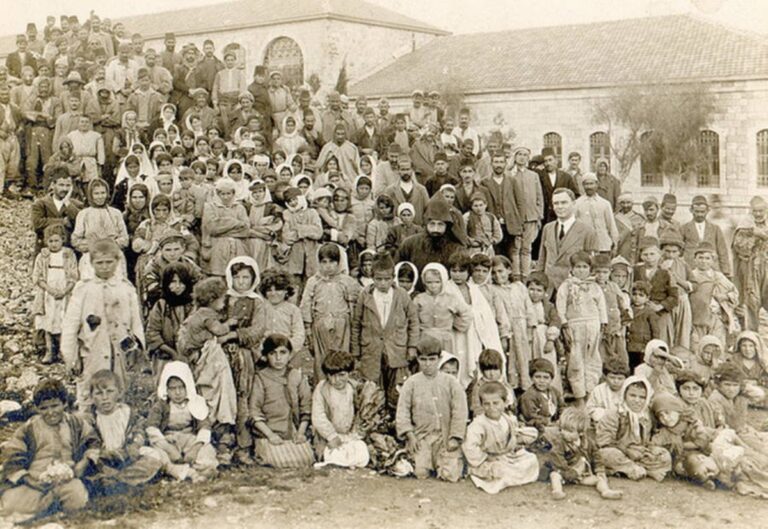

The suffering extended beyond death. Survivors who reached Aleppo or refugee camps in the Middle East bore physical and psychological trauma. Many were left with permanent disabilities, illnesses, and deep psychological scars. Armenian women who survived in captivity often hid religious symbols under their clothes, whispered Armenian prayers in secret, or tried to preserve fragments of their cultural identity despite relentless pressure to assimilate.

The Armenian Genocide obliterated entire family lines. Countless women vanished without records or graves; their names were lost, their stories silenced. Many survivor accounts were recorded decades later by children and grandchildren, reconstructing what little could be salvaged of these lives.

Today, scholarly research, survivor memoirs, and archival documentation provide evidence of the specific forms of violence Armenian women faced — forms shaped by both genocidal intent and patriarchal violence. The destruction of Armenian women was not an accidental byproduct of war; it was a deliberate part of the Ottoman campaign to annihilate the Armenian people.

Armenian Women and Resistance: The Fedayis

Among the most remarkable yet often overlooked chapters of the Armenian Genocide is the story of the Armenian women who actively resisted annihilation. While countless women endured unimaginable suffering, some took up arms to defend their communities, joining local self-defense units known as fedayis (freedom fighters).

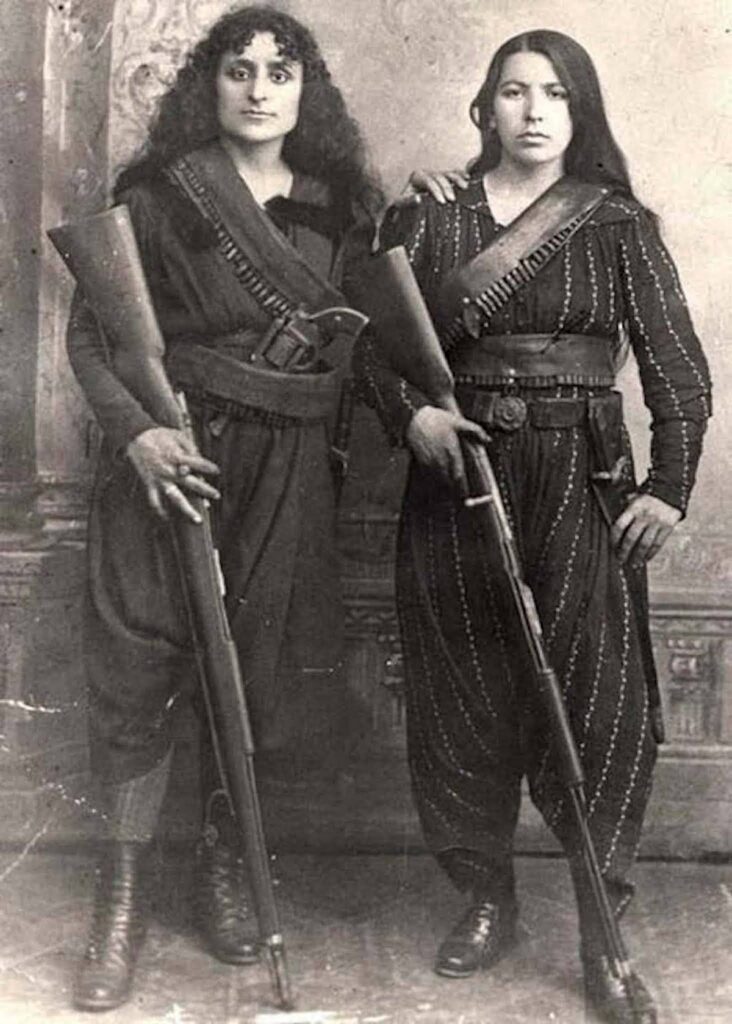

The photograph above depicts two Armenian women fedayi fighters, armed with bandoliers and rifles, captured in a rare historical portrait. These women stand as powerful symbols of defiance against the Ottoman Empire’s systematic campaign of extermination.

In regions such as Zeitun, Van, Shabin-Karahisar, and Musa Dagh, Armenian resistance movements emerged as acts of survival. Women played crucial roles—not only as fighters but also as couriers, nurses, intelligence gatherers, and supporters of the armed struggle. Their participation defied both Ottoman oppression and traditional gender expectations, demonstrating extraordinary resolve under catastrophic circumstances.

For many women, resistance was not merely a choice but a last resort. As Ottoman forces encircled Armenian villages and massacres began, entire communities—men, women, and children—mobilized to defend themselves. Women fighters were recorded holding defensive positions, leading guerrilla attacks, and, in some instances, dying alongside male combatants rather than surrender to a fate of rape, enslavement, or forced conversion.

This photograph is a rare and invaluable testament to the active agency of Armenian women during the Genocide. It challenges prevailing images of women solely as passive victims and underscores the multifaceted ways in which Armenian women confronted the machinery of destruction. By preserving and exhibiting such images, we not only honor their bravery but also restore a critical dimension to the historical memory of the Armenian people.