By the Armenian Genocide Museum of Canada

Photo above: Students in an Azerbaijani school perform the Grey Wolves salute — a symbol of Turkish ultranationalism and anti-Armenian ideology. Behind them, nationalist slogans and pan-Turkist flags reinforce a deeply embedded ecosystem of hate. The phrase: “Ey Türk! Titre ve kendine dön” (“Oh Turk! Tremble and return to yourself”) is a quote attributed to the ancient Göktürk inscriptions. It invokes ethnic pride and a call to action for Turks to embrace their national identity — often in a militarized, supremacist context. Although Azerbaijan is a separate country, it shares deep linguistic, cultural, and ideological ties with Turkey through a shared Turkic identity. This pan-Turkist worldview fuels state-sponsored Armenophobia in both countries, uniting them in narratives that glorify violence and historical denial.

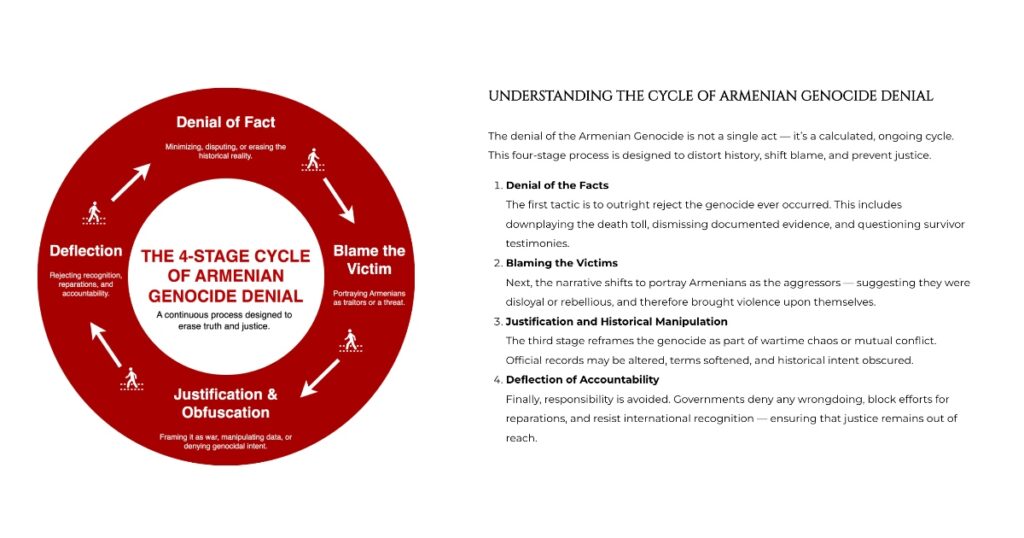

The Armenian Genocide was not simply a historical tragedy—it was the brutal climax of long-standing Armenophobia embedded in the political, cultural, and nationalistic frameworks of the Ottoman Empire. And unlike many genocides that end with attempts at reconciliation or reflection, the Armenian experience is uniquely marked by a continued legacy of hatred that has only shifted shape.

The Genocide was supposed to be the end. But for the survivors, it was the beginning of a century of erasure, denial, and renewed persecution.

Hate Before and After the Armenian Genocide

Even before 1915, Armenians in the Ottoman Empire were branded as “infidels” and subjected to massacres, pogroms, and discriminatory laws. The Genocide itself was carried out not only with ruthless efficiency, but with cultural and spiritual violence: the destruction of churches, schools, manuscripts, and graveyards was intentional. It wasn’t just about eliminating people—it was about eliminating a people.

Turkey, to this day, refuses to acknowledge this crime. In Turkish textbooks, Armenians are often portrayed as traitors. Genocide denial isn’t just passive—it’s active. The descendants of survivors are still treated as enemies. The state still criminalizes memory. In Turkey, surviving the Armenian Genocide did not protect Armenians—it branded them.

Azerbaijan: A Nation Built on Armenophobia

But perhaps nowhere is Armenophobia more institutionalized today than in Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan hasn’t simply adopted hatred of Armenians as policy—it has built an entire ecosystem of national identity around it. From school curricula to state media, from military rhetoric to children’s cartoons, Armenians are dehumanized, vilified, and painted as existential threats. This isn’t a fringe view—it’s the national narrative.

It is as if without Armenophobia, Azerbaijan would lose its glue. Strip it away, and the entire mythos that keeps the regime together begins to collapse. Hatred of Armenians is not a side effect; it is the scaffolding.

The recent ethnic cleansing of 120,000 Armenians from Artsakh in 2023 was not a moment of outrage for Azerbaijani society—it was celebrated. Videos surfaced of Azerbaijani soldiers mocking and torturing Armenian civilians. Streets in Baku are named after murderers of Armenians. Statues are built to glorify them. Children grow up not only without exposure to Armenians—but with the deep-rooted belief that Armenians must not exist.

This is not just racism. This is national purpose.

Why Memory Matters

When Adolf Hitler famously asked, “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”—he was counting on silence.

But we speak. At the Armenian Genocide Museum of Canada, we refuse to let silence bury truth. Memory is resistance. Preservation is power.

We document not just the past but the present—because the Armenian Genocide did not end in 1915. It continues in every act of denial, every hate-fueled policy, every erased church, every displaced family, every unspoken truth.

Armenian hate is unique not just because it was so brutal, but because it never stopped.

We speak today. We will speak tomorrow.

And we will never stop.