the Armenian Genocide

Prelude to the Armenian Genocide: The Hamidian Massacres (1894-1896)

The roots of the Armenian Genocide can be traced back to the final decades of the Ottoman Empire, particularly during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The Armenian population, a Christian minority within the empire, had long suffered from systemic discrimination, oppressive taxation, and lack of legal protections. By the late 19th century, Armenian intellectuals and reformists began advocating for equal rights and autonomy within the Ottoman framework.

In response, the Ottoman authorities, fearing separatist movements and viewing the Armenian population as a potential threat, unleashed a wave of violence that became known as the Hamidian Massacres. Between 1894 and 1896, Ottoman forces and irregular Kurdish groups slaughtered an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 Armenians. These massacres served as a grim precursor to the more systematic extermination that would take place two decades later.

The Young Turks and the Rise of Nationalism

In 1908, the Young Turk revolution brought an ostensibly progressive government to power. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the ruling party, initially promised reforms and equality for all ethnic groups within the empire. However, their vision of a homogenized Turkish nation soon led to policies of exclusion and persecution. Following the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), the Ottoman Empire suffered territorial losses, leading to an intensified sense of Turkish nationalism and a deepened suspicion of Christian minorities, particularly Armenians.

Prior to World War I, the Armenian community in the Ottoman Empire, particularly in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), held significant economic influence. Armenians were prominent in various sectors, including banking, commerce, and craftsmanship. Notably, they had a near-total monopoly in jewelry manufacturing and were influential in the banking industry, with dedicated quarters in Galata and Hasköy.

In Aleppo, Armenian merchants like Khwaja Petik Chelebi and his brother Khwaja Sanos Chelebi dominated the silk trade from the late 16th to the early 17th centuries, establishing extensive trade networks across Anatolia, Persia, and India.

Despite being a minority, Armenians were overrepresented in commerce, which led to resentment and suspicion among the Muslim populace. This economic prominence contributed to tensions, as some Ottoman authorities and segments of the Muslim population viewed the Armenians’ success with envy and distrust.

Regarding demographics, estimates of the Armenian population in Constantinople before 1915 vary. In 1913, Armenians comprised approximately 15% of the city’s population, numbering around 163,670 individuals. This significant presence further underscored their influence in the empire’s capital.

The combination of the Armenians’ economic success and their substantial presence in key urban centers like Constantinople contributed to the Ottoman authorities’ perception of them as internal enemies, especially amid the heightened paranoia of World War I.

The Outbreak of World War I and the Implementation of the Armenian Genocide (1915-1923)

With the advent of World War I in 1914, the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers, engaging in battles on multiple fronts. As the war progressed, the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) sought to consolidate its power and eliminate perceived threats to its nationalist agenda. The Armenian population, which had long been marginalized and subjected to discriminatory policies, became a convenient scapegoat. Ottoman authorities accused them of harboring sympathies for the Russian Empire, a claim rooted in little more than the existence of Armenian communities on both sides of the Ottoman-Russian border.

This accusation was not only baseless but deliberately manufactured as part of a broader strategy to demonize and dehumanize the Armenian population. The Ottoman leadership knew that wartime propaganda could be an effective tool in inciting fear and hostility among the broader Muslim population, thereby justifying their premeditated plans for mass deportations and extermination. The accusation of disloyalty served as a pretext to frame Armenians as an existential threat, paving the way for their systematic destruction.

In reality, Armenian political and religious leaders had made numerous efforts to demonstrate loyalty to the Ottoman state, and the majority of Armenians, including those in the Ottoman military, had no involvement in any subversive activities. Nonetheless, the CUP’s propaganda machine successfully painted Armenians as traitors, a narrative that was used to rationalize their forced marches into the Syrian desert, mass executions, and other atrocities.

This falsification was not an isolated incident but a classic case of state-sponsored incitement, designed to prepare the populace for genocide. By portraying Armenians as enemies within, the Ottoman regime sought to ensure public acquiescence, if not outright participation, in the genocide that followed.

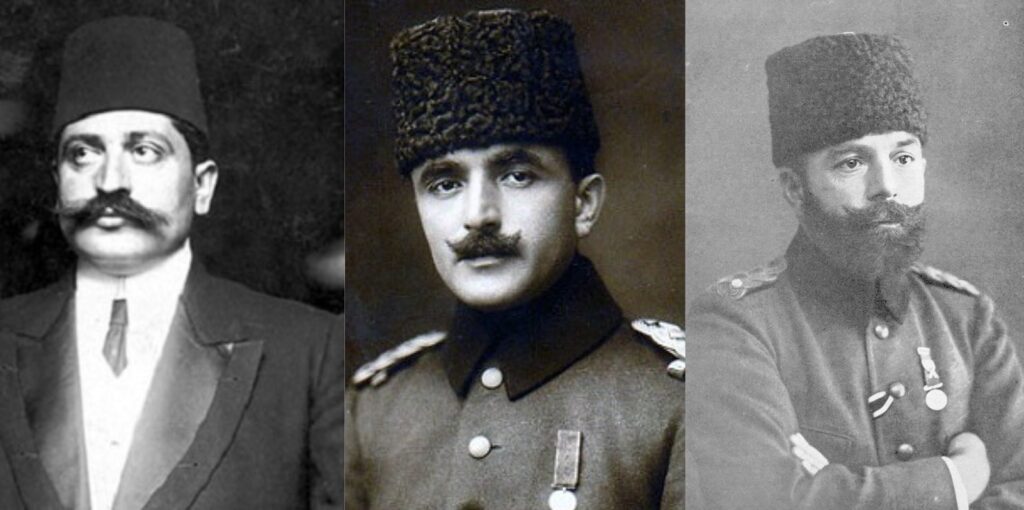

THE MASTERMINDS OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE

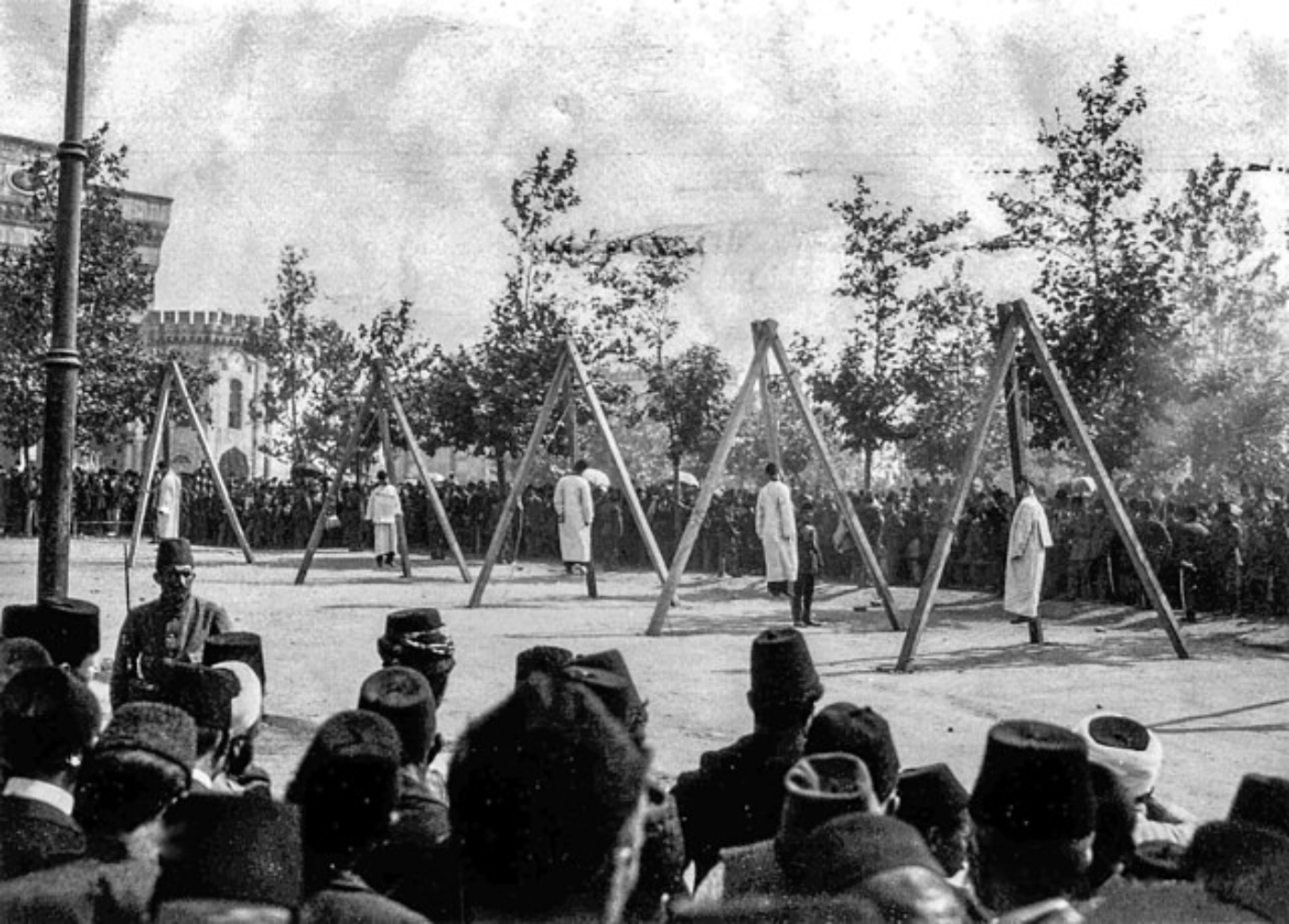

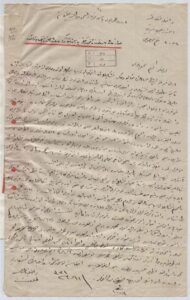

The Armenian Genocide was meticulously planned and executed by the highest ranks of the Ottoman government, particularly the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). At the center of this orchestrated extermination were the so-called “Three Pashas”—Mehmed Talaat Bey (later Talaat Pasha), Ismail Enver Pasha, and Ahmed Djemal Pasha—who wielded absolute power over the empire during World War I. Talaat Pasha, the Minister of the Interior and later Grand Vizier, was the chief architect of the Genocide. He personally issued orders for mass deportations and executions, overseeing the logistical network that ensured the annihilation of the Armenian population. Enver Pasha, the Minister of War, used the pretext of military necessity to justify the slaughter, blaming Armenians for the Ottoman Empire’s military failures. Djemal Pasha, the Governor of Syria and Minister of the Navy, imposed brutal measures against Armenian refugees in the Syrian deserts, particularly in Deir ez-Zor, where thousands perished under his direct supervision.

Beyond these three, other high-ranking officials played pivotal roles in carrying out the Genocide. Dr. Mehmed Nazim, a leading figure in the CUP and an ideological fanatic, was one of the primary proponents of racial extermination, openly advocating for the destruction of Armenians as a means to create a homogenous Turkish state. Behaeddin Shakir, the head of the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization), oversaw death squads composed of criminals and paramilitary units, which carried out mass killings with ruthless efficiency. These operatives were responsible for some of the most gruesome massacres, including the drowning of Armenian women and children in rivers, the burning of entire villages, and the operation of primitive gas chambers in Deir ez-Zor, where victims were asphyxiated in caves set on fire.

After the war, these masterminds of genocide fled the collapsing Ottoman Empire. Mehmed Talaat Pasha was assassinated in Berlin in 1921 by Soghomon Tehlirian, an Armenian survivor who carried out the execution as part of Operation Nemesis, a clandestine campaign to bring Ottoman war criminals to justice. Ismail Enver Pasha was later killed in battle in Central Asia, while Ahmed Djemal Pasha met his end in an assassination in Georgia in 1922. Though some faced retribution, many other perpetrators escaped consequences, with some even reintegrating into the Turkish Republic’s political and military elite. Their legacy of genocide denial continues to shape modern Turkish policy.

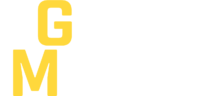

The Beginning: Arrests and Deportations (April 24, 1915)

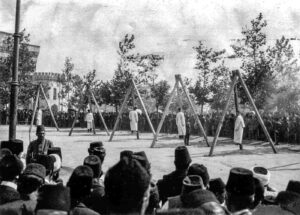

On the night of April 24, 1915, the Ottoman government initiated the first phase of the Armenian Genocide with a calculated and brutal maneuver: the arrest of hundreds of Armenian intellectuals, political leaders, clergy, journalists, and cultural figures in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). These individuals represented the backbone of Armenian society—the thinkers, organizers, and voices of a people whose historical presence in the region spanned millennia. Depriving the Armenian community of its leadership was a deliberate first step in a broader campaign of systematic annihilation.

Those arrested were deported to the interior of Anatolia, where they were either executed outright or perished under inhumane conditions. Their deaths were not incidental but central to the Ottoman authorities’ genocidal blueprint—by eliminating the minds and advocates of Armenian identity, they sought to render the entire people defenseless, leaderless, and incapable of resistance. This was not simply repression; it was an act of erasure, ensuring that the Armenian population would be easier to target in the mass deportations and massacres that followed.

This date, April 24, 1915, would come to symbolize not only the beginning of the Armenian Genocide but also the resilience of the Armenian people. In the decades that followed, as survivors scattered across the world—many settling in the Middle East, Europe, and North America—the memory of this day became sacred. What was once a night of horror transformed into a day of remembrance, reflection, and defiance.

Each year, Armenians across the globe gather on April 24 to honor the victims and demand recognition of the Genocide that was denied for over a century. The day serves as both a solemn commemoration and a rallying cry against historical revisionism, ensuring that the truth of 1915 remains indelible. From the streets of Yerevan to the diasporan communities of Los Angeles, Paris, Buenos Aires, and beyond, April 24 has become a unifying moment for Armenians—a day when a fragmented people, shaped by exile and survival, reaffirm their collective identity and their unwavering pursuit of justice.

Mass Deportations and Death Marches

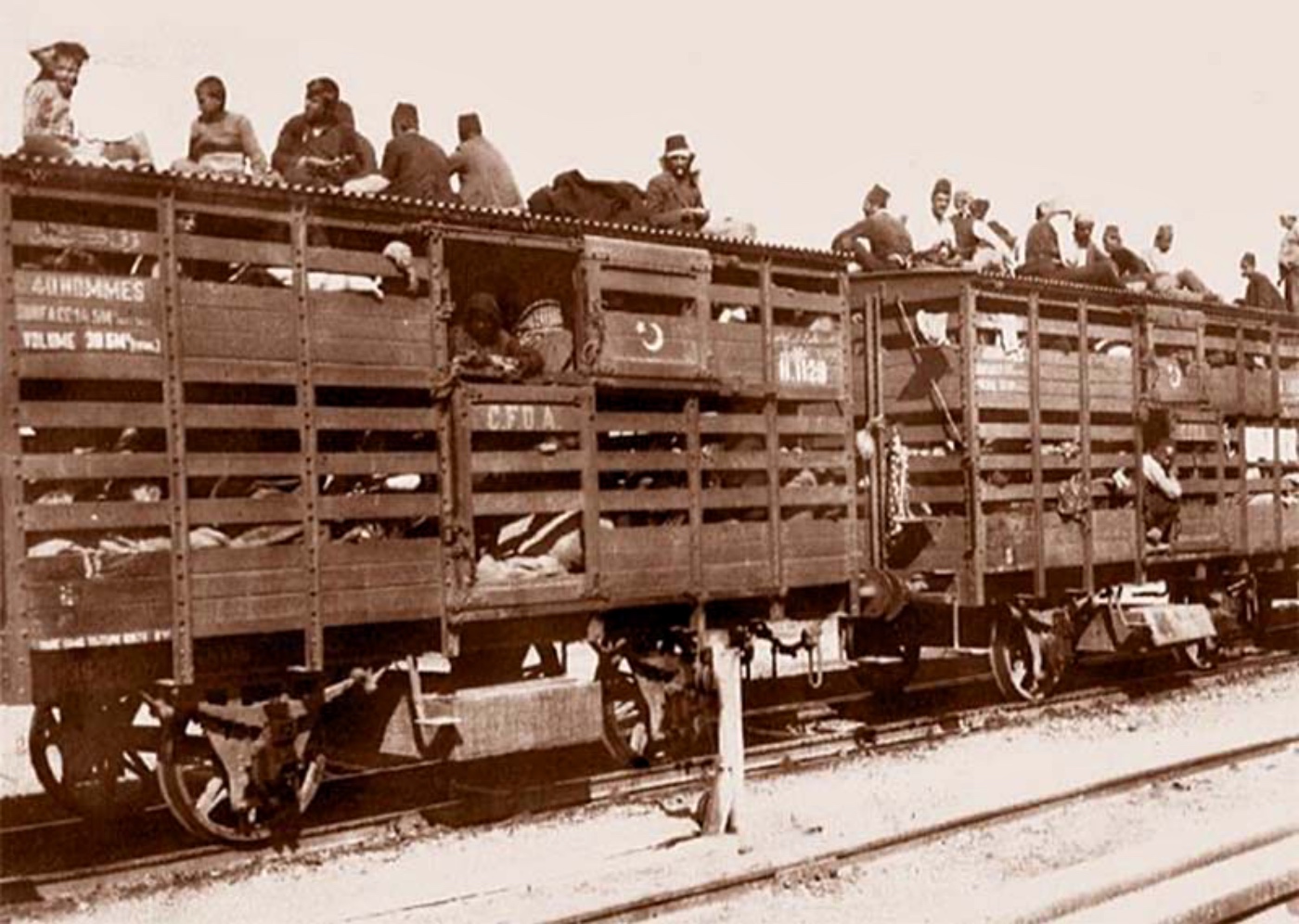

Shortly after the systematic arrest and execution of Armenian intellectuals, the Ottoman authorities escalated their genocidal campaign by ordering the forced deportation of Armenian populations from their ancestral lands in Anatolia. What was framed as a “resettlement” was, in reality, a death sentence. Entire villages and towns were emptied as men, women, and children were driven from their homes under the pretext of wartime security.

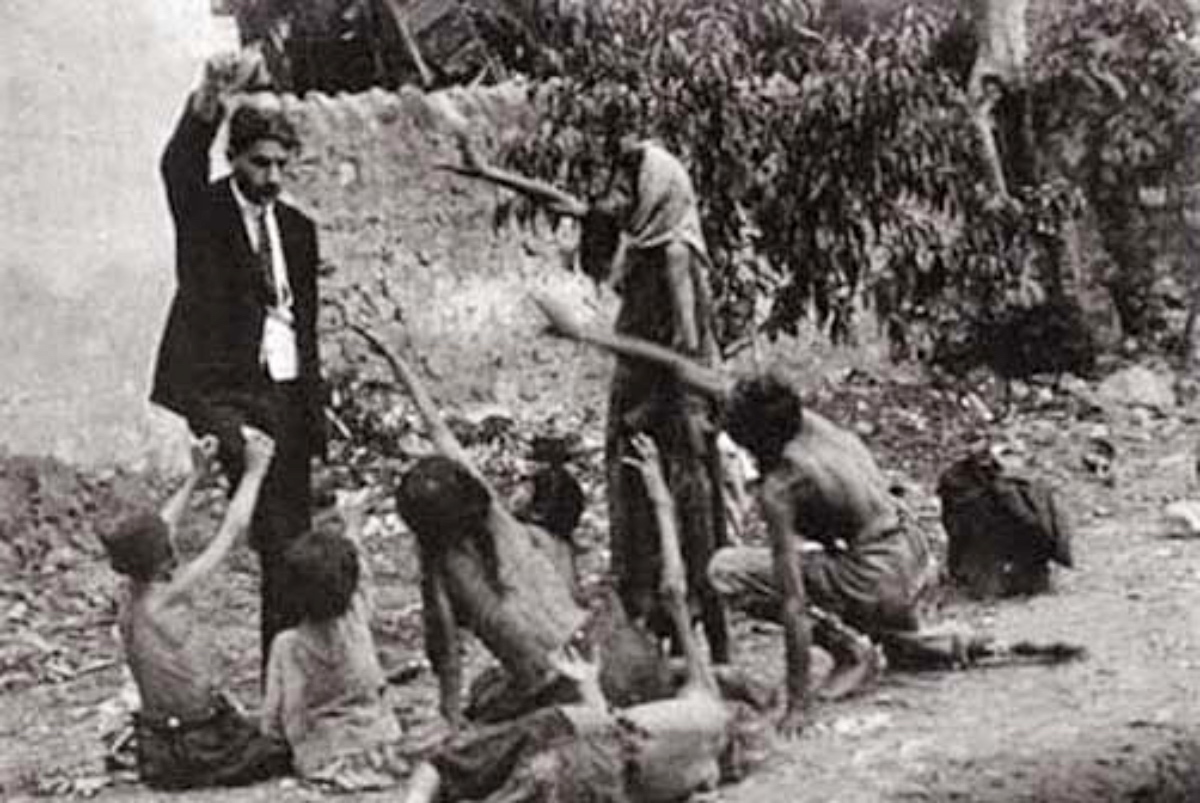

Men were frequently executed outright, often gathered in groups and shot, bayoneted, or burned alive—methods designed not just for extermination but for terror. Without their husbands, fathers, and brothers to protect them, women, children, and the elderly were left defenseless, forced into grueling death marches toward the Syrian Desert. These marches were deliberately designed to maximize suffering and fatalities. Ottoman forces and Kurdish paramilitary groups, acting under government orders, systematically brutalized the deportees. Many were subjected to rape, abduction, and human trafficking, with young Armenian girls sold into slavery or forcibly converted to Islam.

Deprived of food, water, and medical care, the marchers collapsed along the scorching, barren roads. Mothers, too weak to continue, were forced to abandon their infants. Children, delirious with thirst, resorted to drinking their own urine or the blood of dying relatives. The bodies of the dead and dying littered the roads, left unburied as a warning to those who still clung to life. The desert became a vast, open-air graveyard.

For those who survived this hellish ordeal, an even more horrifying fate awaited. Many were herded into concentration camps in Deir ez-Zor, Syria—the final stage of their extermination. Stripped of any remaining humanity, the survivors faced mass executions, often thrown into caves and gorges where they were burned alive or suffocated. In some cases, the Ottomans implemented primitive gas chambers—sealed caves or underground pits where victims were packed together and exposed to fire, suffocating in toxic fumes as their bodies burned from the intense heat. This was genocide in its most grotesque and premeditated form—an industrialized method of mass murder, long before the world would recognize its echoes in the gas chambers of Nazi Germany.

The annihilation was not merely physical but cultural and existential. Churches, monasteries, and schools—centuries-old institutions of Armenian identity—were desecrated or converted into mosques and military outposts. Sacred manuscripts, priceless artifacts, and entire archives of Armenian heritage were deliberately destroyed, an attempt to erase an entire civilization from history.

Massacres and Atrocities

Throughout the Armenian Genocide, entire villages and towns were systematically destroyed, erasing centuries-old Armenian communities from their homeland. Ottoman forces, alongside Kurdish and Circassian militias, carried out mass executions, often marching men to isolated locations where they were shot, bayoneted, or hacked to death. Women, children, and the elderly were subjected to unspeakable brutality—drowned en masse in rivers, burned alive in churches and caves, or forced into the desert, where they perished from starvation and exposure.

Sexual violence was widespread, with Armenian women and girls abducted, trafficked, and subjected to rape and forced concubinage. Many were forcibly converted to Islam and taken into Turkish and Kurdish households, while others were branded or mutilated as a form of humiliation and control.

Foreign diplomats, missionaries, and relief workers documented these atrocities, sending reports that detailed the extent of the suffering. Graphic testimonies from survivors and witnesses described bodies littering roadsides, rivers choked with corpses, and death marches stretching for miles. Despite global outcry, the international response was largely limited to formal condemnations, humanitarian aid, and public appeals—efforts that, while significant, ultimately failed to halt the extermination.

Resistance and Survival

Despite facing overwhelming odds, Armenians mounted acts of resistance. The most notable uprising occurred in Van (April-May 1915), where Armenian fighters held off Ottoman forces for weeks until Russian troops temporarily liberated the city. Other instances of defiance took place in Musa Dagh and various other locations, where small groups of Armenians managed to escape the systematic slaughter.

The Role of Foreign Observers

Foreign diplomats, journalists, and relief workers provided crucial documentation of the Armenian Genocide. U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau Sr., was one of the most outspoken figures, repeatedly warning the U.S. government about the Genocide. Eyewitness reports from missionaries and journalists, such as Armin T. Wegner and the American Committee for Relief in the Near East, helped provide contemporary evidence of the atrocities.

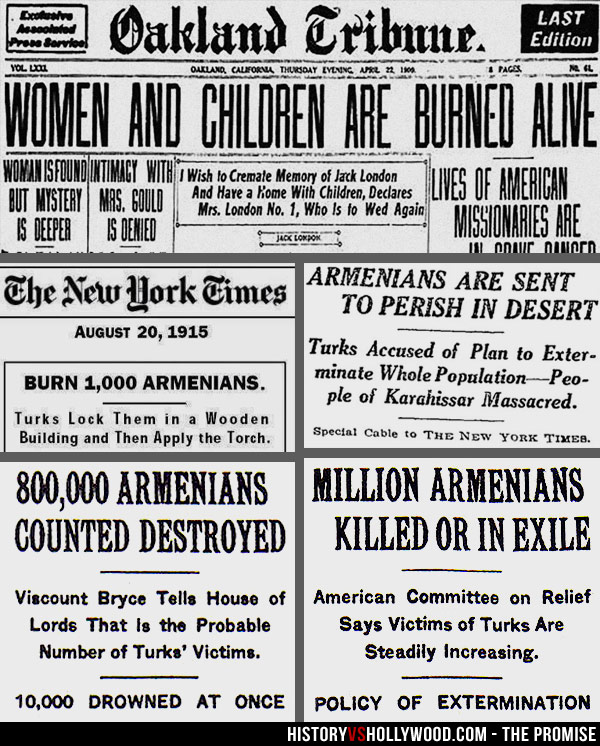

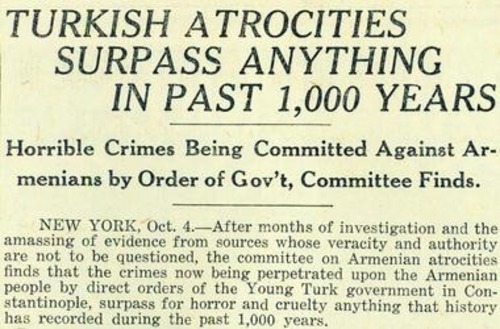

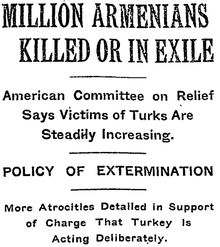

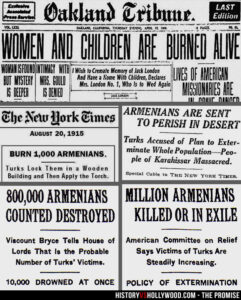

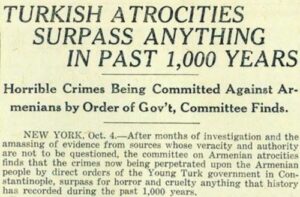

The horrors of the Genocide were widely reported in the international press, with The New York Times alone publishing over 145 articles on the massacres between 1915 and 1916, many carrying explicit titles such as “Wholesale Massacres of Armenians by Turks” and “Appeal to the Ottoman Empire to Stop Massacres.” These reports described in grim detail the death marches, mass executions, and starvation that Armenians endured, dispelling any notion that these events were isolated or exaggerated. The global response, though largely limited to humanitarian aid at the time, underscored the undeniable truth that the world was watching, even as governments hesitated to intervene.

Among those who documented the Genocide, Armin T. Wegner, a German soldier and medic stationed in the Ottoman Empire, took some of the only known photographs of the atrocities—images that would later serve as undeniable evidence of the Genocide. His smuggled photographs depicted emaciated Armenian refugees, mass graves, and the unimaginable suffering in the concentration camps of Deir ez-Zor. Similarly, the American diplomat Leslie Davis, stationed in Harput, meticulously chronicled the mass killings he witnessed, his reports emphasizing the scale and premeditated nature of the extermination.

Relief organizations also played a crucial role in documenting and alleviating Armenian suffering. The American Committee for Relief in the Near East (later known as Near East Relief) spearheaded one of the largest humanitarian efforts of the early 20th century, raising over $100 million (equivalent to billions today) to aid survivors. Their efforts helped rescue thousands of Armenian orphans who had been left to die in the deserts of Syria. Countless missionaries and aid workers risked their lives to smuggle out testimonies, photographs, and detailed reports of what they had witnessed.

Despite these efforts, political inaction and geopolitical interests prevented meaningful intervention at the time. Still, the records they compiled would later serve as the foundation for historical recognition of the Armenian Genocide. Morgenthau’s memoir, Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story, and Wegner’s harrowing photographs became pivotal pieces of evidence, referenced by scholars, activists, and even Raphael Lemkin—the legal scholar who later coined the term genocide—as undeniable proof of the systematic annihilation of the Armenian people.

Today, these testimonies remain crucial in the ongoing fight for global recognition of the Genocide, challenging denialist narratives and ensuring that the voices of those who bore witness are never silenced.

The End of the Armenian Genocide and Its Aftermath

By 1923, following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Armenian Genocide had resulted in the deaths of over 1.5 million Armenians. The survivors, many of whom were orphaned children or destitute refugees, scattered across the world, forming the Armenian Diaspora in countries such as the United States, France, Argentina, Lebanon, and Canada.

Denial and Historical Legacy

Despite overwhelming historical evidence, the Turkish government has consistently denied the Armenian Genocide, arguing that the deaths were a consequence of war rather than a premeditated extermination. This denial has been met with international condemnation, with numerous countries officially recognizing the Genocide, including Canada, which formally acknowledged it in 2004.

The Armenian Genocide remains one of the darkest chapters in modern history. Its legacy continues to shape Armenian identity, international law regarding crimes against humanity, and global discussions on human rights and genocide prevention. The Armenian Genocide Museum of Canada is dedicated to preserving the memory of these events, ensuring that future generations remember and learn from this tragic past.

“Remembrance is Our Promise.”